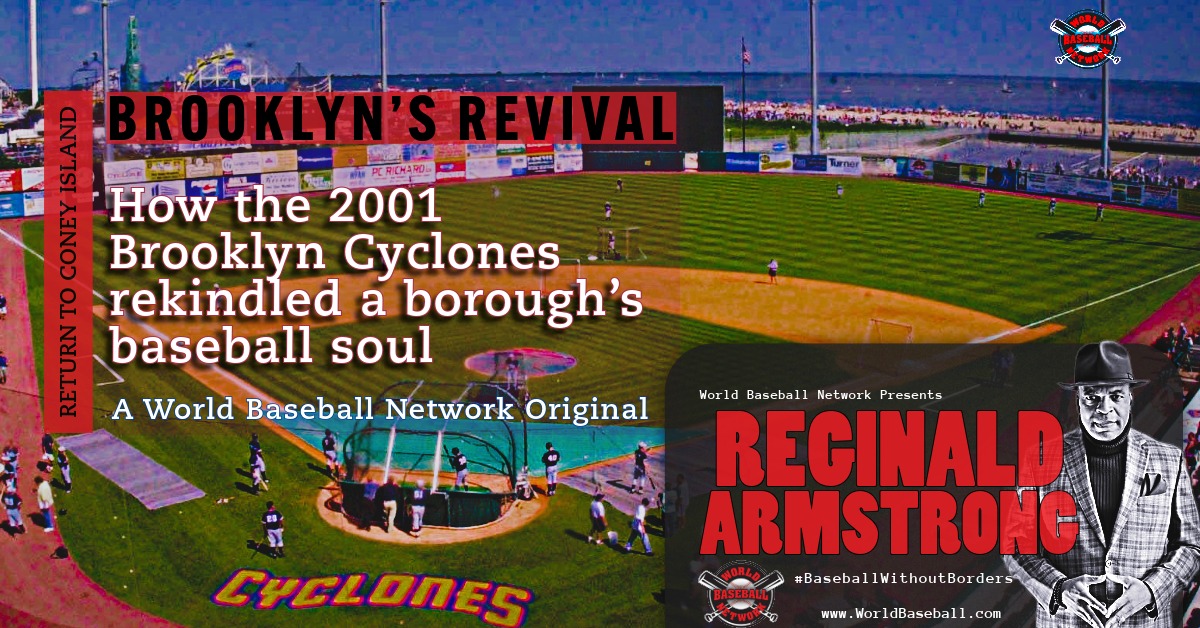

In 2001, Brooklyn welcomed back professional baseball after a 44-year absence, transforming KeySpan Park into a cultural shrine. Nestled in Coney Island, steps from the Riegelmann Boardwalk, with the Atlantic’s sandy beaches just beyond the outfield wall, the ballpark was framed by the Coney Island Cyclone roller coaster (since 1927) and the dormant Parachute Jump (a 1939 relic awaiting its LED revival). The salty sea breeze and clatter of nearby rides set a nostalgic stage for nearly 9,000 SRO fans nightly, packing sold-out stands with Brooklyn’s defiant energy.

Editorial note: In 2025, the Brooklyn Cyclones—now in their first full-season campaign in the South Atlantic League—clinched their third league championship, sweeping the postseason. A quiet triumph worth honoring.

Mini-Major League Milieu

In New York, a major league city, Brooklyn’s 2001–2002 seasons transcended minor league status. “Mr. Mayor,” Rudy Giuliani—a proud Brooklyn boy himself—sat behind our broadcast perch more than once, while Fred Wilpon and his son Jeff, the club’s de facto boss, held court in luxury suites just to our left. Baseball royalty—Duke Snider, John Franco, Jim Palmer, Joe Pignatano, Jackie and Rachel Robinson’s daughter Sharon, CNN’s Larry King, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Tommy Holmes, Edgardo Alfonzo—and countless others basked in the scene.

The stands sparkled with former and current professional athletes, CEOs, and Brooklyn-connected personalities of every stripe—rappers, Broadway icons, Wall Street executives, and curious locals alike. Year one and into year two, the ballpark became a magnet for anyone drawn to the borough’s heartbeat. From Spike Lee’s Harper’s Bazaar shoot at second base—featuring Cyclones players like Tyler Beuerlein and Brett Kay—to pitchers Mike Cox and Ross Peeples appearing on MTV’s Total Request Live with Carson Daly, Brooklyn’s revival in 2001 wasn’t just local. It was cultural. It was televised. It was threaded into the fabric of a borough reclaiming its baseball soul.

Brooklyn’s Emotional Bridge

For fans who saw the Boys of Summer—Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, Carl Erskine, Gil Hodges—at Ebbets Field, listened to Red Barber and Connie Desmond before Vin Scully, or felt Walter O’Malley’s exit (with Robert Moses as the true culprit), Brooklyn’s return was a resurrection.

Aerial view of Ebbets Field in Brooklyn as the New York Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers played before almost 35,000 fans in the third game of the World Series on Oct. 4, 1941. The Yankees won by a score of 2-1. (AP Photo)

The Ebbets Field Apartments as they stand today—a living structure built atop borough memory, where “Dem Bums” once echoed and civic pride still pulses.

Listeners from around the globe tuned into our internet broadcasts, reconnecting to that intimate bandbox on Bedford Avenue. The Cyclones’ success was secondary; the real story was the Brooklyn bridge—not the East River span, but the emotional one restored after 44 years of heartbreak.

In 2001, those aged 55 to 65+ (who were 9 to 19+ when the Boys of Summer won in ’55) were the last cohort with living memory of the Dodgers before their departure. They carried the borough’s baseball soul—its heartbreak, its pride, its rhythm.

Brooklyn, if a city alone, would rank as America’s third largest. In 2001–2002, it pulsed as a kingdom reclaiming its baseball crown.

The Catbird Seat: Voicing Brooklyn’s Soul

As the founding co–radio voice with the late Warner Fusselle, successor to Mel Allen on This Week in Baseball, I embraced a lifelong avocation turned vocation. We christened our alfresco radio booth “The Catbird Seat,” borrowing Red Barber’s pet phrase, our perch positioned in front of the glass-enclosed press box, high above home plate—adjacent to the luxury suites just to our left. Seated closest to the suites, I found myself immersed in Brooklyn’s electric, carnivalesque mise en scène.

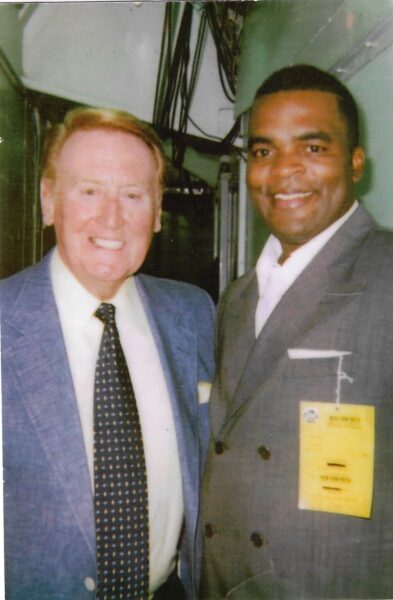

As a student of the craft since adolescence, I studied the primogenitors—the all-time greats: Graham McNamee, Bill Stern, Red Barber, Connie Desmond, Gene Kelly (not the actor), Mel Allen, Lindsey Nelson, Jack Buck, Ernie Harwell, and so many more. This was my classroom. Yet among them, the Headmaster and most mellifluous of all, Vin Scully, stood unmatched.

A slight acquaintance of mine, Vin welcomed me into his broadcasting booth at Shea Stadium on August 6, 1999—Octavio Dotel outdueling Chan Ho Park—where I sat with him, quietly in awe, for four unforgettable innings as his Dodgers faced the Mets. Between innings, we’d laugh and chat before the countdown back to live coverage—his voice beaming back to Southern California on KTTV Channel 11 for the first three innings, then KLAC 570 radio for the middle stretch, before returning to television. He painted and narrated the game, edifying and delighting millions while I sat behind him, quietly absorbing the master at work.

Opening Night Spectacle

Brooklyn’s first game was June 19, 2001, away in Jamestown, NY for four games, followed by two in Vermont. The home opener on June 25, 2001 vs. Mahoning Valley Scrappers drew ESPN interest, all major NYC TV stations, USA Today, and aired locally on Channel 13, with David Hartman—a Dodgers fanatic who frequented Ebbets Field and former Good Morning America host—on the call, partnered with Dave Sims, now the 2025 Yankees’ radio voice.

Mike Jacobs’ sacrifice fly scored Leandro Arias in the 10th to win the home opener, sending the crowd wild. As the media swarmed him outside the first base bag, in foul territory near the dugout under beaming lights, visible from our perch, I said on-air with a wry smile, “Warner, Jake looks like a Senator standing there fielding questions!” It was a night etched in Brooklyn’s memory.

Carl Erskine’s Brooklyn Opening Day

In Jamestown, a surprise last-minute announcement revealed that Carl Erskine—Brooklyn Dodgers’ accomplished right-handed pitcher—would play the national anthem on harmonica, ceremonially launching Brooklyn’s first professional baseball game and radio broadcast since the days of Sandy Koufax, Carl Furillo, Vin Scully, and Jerry Doggett.

A key figure in the Dodgers’ golden era, Erskine was a five-time National League pennant winner, a 1955 World Series champion, and the owner of two no-hitters. Over his 12-year career, he won 122 games, struck out 981 batters, and set a World Series record with 14 strikeouts in a single game.

As our—and Brooklyn’s—first guest, he stayed for an inning, reminiscing about Brooklyn, his career, and the borough’s baseball rebirth. The next afternoon at Jamestown’s Lakewood Lodge, he shared Jackie Robinson tales, recounting abuse that was especially vile toward Jackie—and intolerable to the team—and Gene Hermanski’s rally amid an assassination threat: “Let’s all wear number 42, so the bastard won’t know who to shoot!”

In the face of Erskine’s haunting recollection of just a fraction of the hardships Jackie endured nearly 80 years ago, we in attendance all roared with laughter at the story’s humor—because sometimes, humor was the only shield against the hatred that surrounded them. It was not a joke, but a moment of shared resilience—born from solidarity, survival, and the hard-won accomplishment of a man who didn’t just bear the weight of an unjust world—but carried it forward into victory. Without that triumph, the world might never have known his name—and Branch Rickey might never have stayed the course.

Brooklyn Dodgers’ second baseman Jackie Robinson sits dejectedly in the clubhouse at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, N.Y., Oct. 7, 1952, following the Dodgers’ loss to the Yankees in the finale of the 1952 World Series. The Dodgers have gone up against the Yanks in three World Series but have never defeated them. (AP Photo)

When Erskine returned to Brooklyn the following year, after all those years since he played, I asked if he remembered when I shook his hand after the event and thanked him for sharing Jackie stories, especially that one. He said yes—and appreciated me particularly for saying it, an act of grace on his part. The dignity he carried then, and I imagine into his death, spoke volumes, reminding me that the bonds forged in baseball stretch far beyond the game itself.

Iconic On-Air Interviews: From Internet Only to AM Radio

Warner and I interviewed legends at our outside Catbird Seat broadcasting position, forging ties to the Boys of Summer. Duke Snider, Jim Palmer, Mayor Giuliani, Sharon Robinson, Spike Lee, and other stars sat between us, sharing Ebbets Field and Brooklyn stories.

These broadcasts streamed globally via internet radio—by 2002, Sporting News Radio WSNR 620 AM aired them, amplifying Brooklyn’s revival, before social media reshaped the landscape—linking Brooklyn’s present to its Dodgers past. From this open-air perch, we embraced the elements—sun, wind, and the distant hum of the ballpark—while the crack of the bat, the roar of the crowd, and the faint strains of ballpark sounds & music filtered through the air into the broadcast, as baseball’s living history unfolded in our conversations.

The Night the Glass Shattered: Chaos in the Booth

One iconic night, Frank Corr—who tied for first in home-run output and hit .302 in 2001—stood out alongside future MLB star Ángel Pagán. He fouled a ball skyward, and it soared over our booth, shattering the massive press-box glass behind us with a thunderous crack across KeySpan Park. Shards rained down, embedding in my hair, scattering across our broadcast table, glinting under the stadium lights—an explosion frozen in time.

Brooklyn’s Dream and a City’s Wound

In 2001, Brooklyn’s team, coached by a stellar staff, shattered NYPL records, charging toward the championship against the Pirates’ Williamsport affiliate. The borough was abuzz with anticipation, old fans in tears at a possible title—Brooklyn’s first since the 1955 Dodgers.

Our Coaching Crew

Early this year (2025) a Cyclones batter quietly matched Devarez’s feat—the first since that night I was there on the mic. By 2002, HoJo took the managerial reins, with Donovan Mitchell Sr.—father of future NBA star Donovan Mitchell Jr.—stepping in as hitting coach. I remember master Donovan Jr., soon to be five years old, weaving through the ballpark with a child’s curiosity, a boy immersed in baseball’s rhythm long before carving his own path in basketball.

Maybe One Day I’ll Switch😂 pic.twitter.com/HIyqdQ9S3T

— Donovan Mitchell (@spidadmitchell) June 14, 2023

Game 2 Buildup

By September 2001, Brooklyn pulsed with hope. Pete Hamill—a New York icon, former editor of the New York Post and Daily News, and Dodgers fan who befriended me at multiple games—spoke of the team’s magic, imagining Jackie and Captain Reese in KeySpan’s seaside glow.

The past felt alive in the present—just as so many older fans had personally shared with me their treasured Ebbets Field stories, reliving what the Dodgers meant to them then, and what this revival meant now.

Fans and the New York media were expected to pack the stands, one win from history—already up one game in the best-of-three series.

Brooklyn’s Revival A Borough’s Heart Reborn: September 11, 2001 — Lower Manhattan. The morning Brooklyn’s baseball dream paused, and the borough’s, the city’s, and America’s soul was tested. This was no metaphor. This was the moment.

That morning, my wife woke me around 8:30 a.m., urging me to watch Peter Jennings report on the World Trade Center’s collapse. The NYPL Championship Series was suspended. Brooklyn, poised for glory, was instead named co-champions—a bittersweet echo of the Dodgers’ 1957 theft. My championship ring, which I hold, carries that weight.

Gil Hodges Day

A defining moment came on Gil Hodges Day, when his number 14 was officially retired at KeySpan Park on September 2, 2001. His lovely widow Joan Hodges, radiant and gracious, was in attendance, embodying the grace and strength of a family bound to baseball history.

Warner and I reflected on-air about the ongoing petition to induct Gil into the Hall of Fame; his number retired in a beautiful ceremony as poignant as it was overdue. It was a day of healing—a moment when Brooklyn once again tied itself to the Boys of Summer, honoring a legacy that refused to fade.

A Lasting Legacy: Brooklyn Never Forgets

I’ve stayed in the shadows since, distanced from Brooklyn’s baseball scene. As I understand it, only a few from 2001 remain: the other Steve Cohen, Sharon Ross-Lundy (then secretary), and Kevin Mahoney (GM there since 2002). David Stearns, now Mets GM, joined in 2004, after my tenure.

HoJo’s Reunion

Years later, at a Mets game at Citi Field, I brought along my nephews, stargazing from behind home plate. Spotting Howard Johnson, I shouted “HoJo!” He turned, smiled, and warmly acknowledged me, asking how I was and sharing how his son, Glen, was faring.

He posed for a pre-game photo—my nephews in the foreground, HoJo visible just beyond the fence behind home plate. A quiet moment, unposed but unmistakably warm, still cherished.

WBN has since released my Nick Loeb Foundation Event interview with Howard Johnson—one of five world champions featured in that legacy series back in June. That conversation threads many of the Brooklyn themes echoed here.

Upon Mature Reflection

Circumstances—misaligned timing, paths crossing where they shouldn’t—led me in a different direction. But I’m proud to have been part of Brooklyn’s history as its first play-by-play voice alongside Warner after 44 long years, helping to rebuild its emotional bridge to its baseball past that still pulses with life.

As the Mets near the 40th anniversary of their 1986 championship—their last to date— Brooklyn’s Second Act turns 25 years next season. These echoes feel especially timely. The borough’s baseball soul—revived, refracted, and remembered. And in the shadow of 9/11, the 2001 arc carries civic weight—threaded through borough memory, cultural inflection, and editorial consequence.

As they say, Brooklyn never forgets.

Contributor’s Note

By day, I help steward a legacy platform in commercial real estate finance—one that’s held its posture through cycles, cities, and sponsors. Across 400+ closings—including 40+ in hotel financing—we’ve built quietly, with rhythm and consequence. If you’re curious about the team behind the cadence, you can find us here.