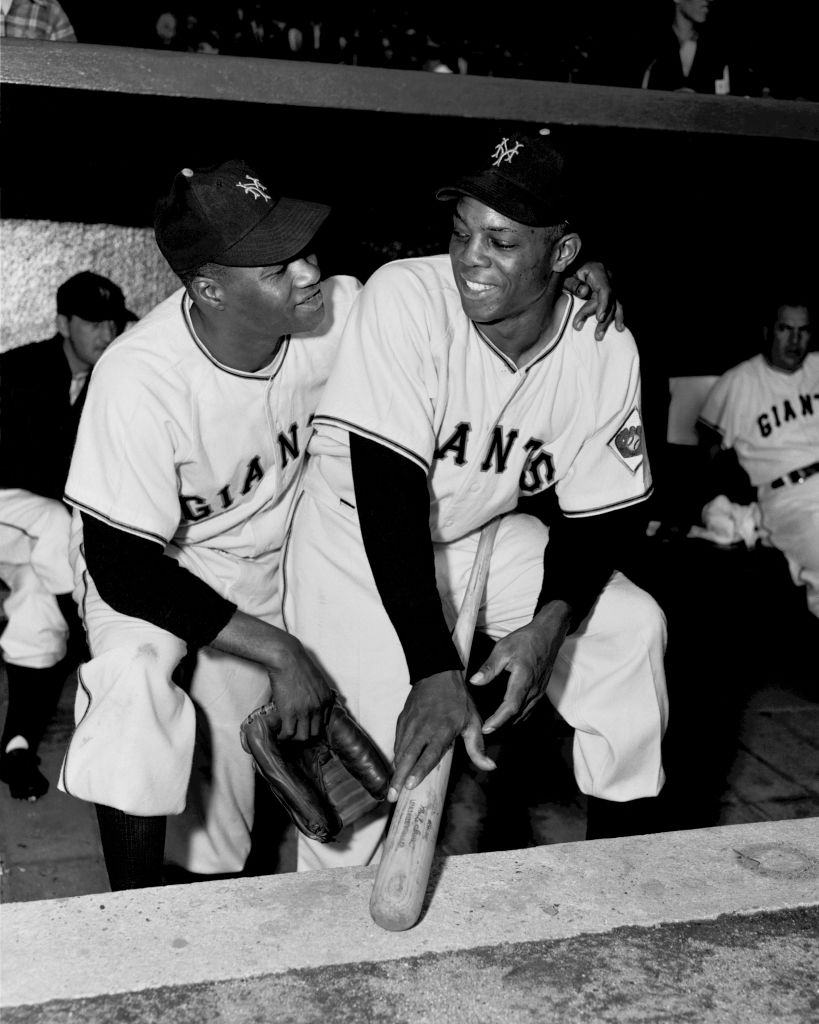

Infielder Hank Thompson and outfielder Willie Mays of the New York Giants pose for a portrait while standing on the dugout steps prior to a game in May, 1951 at the Polo Grounds in New York, New York. (Photo by: 1951 Kidwiler Collection/Diamond Images via Getty Images)

Before instant replay, before a multiple camera telecast, before HDTV or even color TV, Vic Wertz of the Cleveland Indians sent a long fly ball into the cavernous center field of the Polo Grounds in New York City in game one of the 1954 World Series.

A 23-year-old centerfielder for the New York Giants chased it 430-plus feet from home plate, reached over his head, caught the ball, and threw back to the infield in one of Major League Baseball‘s most famous defensive plays of all time.

If there’s one clip, one highlight, one moment that will forever define one of the greatest careers in Major League Baseball history it’s that catch by a young Willie Mays, captured in black and white in New York City 69 1/2 years ago.

Over the course of my life, I’ve probably seen it several hundred times, if not several thousand, despite being too young to have seen Willie Mays play a game for the Giants or Mets, or even earlier for the Birmingham Black Barons in his native Alabama.

On Tuesday evening, as the Double-A Birmingham Barons and Montgomery Biscuits played a game broadcast on MLB network for Rickwood Field in Birmingham, where Willie once played for the Birmingham Black Barons, we got the news that Mays, 93, possibly the greatest baseball player in history, had passed away.

Like so many sons of Giants fans from older generations, I’d been told of Willie Mays’ greatness from an early age by my father, who grew up a Giants fan in New York City and remains one to this day despite not having seen his team play a home game since they called the Polo Grounds home.

I’d heard how he played for the Trenton Giants of the Interstate League, not far from where I grew up in Princeton Junction, N.J., and later read a story, perhaps apocryphal, that Bus Saidt, who later went on to be a Hall of Fame baseball writer for the Trenton Times, was the one who picked him up when he got to town.

The next year, he was with the Minneapolis Millers of the International League when he was called up to the Giants, only the sixth Black man to play in the Major Leagues.

“He was hitting very well. He had a .477 batting average in Minneapolis,” my father, Joel Skodnick, recalled immediately. “Horace Stoneham actually wrote a letter to the Minneapolis paper saying why he had to bring Willie up. Willie, actually, in a way didn’t want to go up, he wanted to stay in Minneapolis for a while.”

It took him four games, but the first of 660 career home runs came against the Boston Braves on May 28, 1951, and he hit 19 more that season, batting .274 on his way to the National League Rookie of the Year. Later that season, when Bobby Thomson clubbed the homer that won the Giants the pennant, Mays was in the on deck circle.

Then the Army called him up from the major leagues, and he missed most of the 1952 and all of the 1953 season, likely leaving us to wonder forever if Willie might have hit No. 715 before Hank Aaron did.

In 1954, not only did Mays make that catch on the way to helping the Giants capture their final World Series title in New York, he won the NL MVP, the NL batting title, and led the Major Leagues in batting average and slugging percentage.

Over that winter, he had two home runs, nine RBI, six doubles, an .855 slugging percentage and led the 1955 Caribbean Series in hits with 11 while playing with Puerto Rico’s Cangrejeros de Santurce.

Playing almost continuously through the 1955 MLB season, he led the Major Leagues with 12 triples, 51 homers, and a .659 slugging percentage the summer after winning the Caribbean Series.

Earlier this year, Major League Baseball announced that statistics from the Negro Leagues would now be considered to be Major League stats, giving Mays an extra 13 games played and 10 more career hits, giving him 3,005 games and 3,293 career hits.

On Thursday, the San Francisco Giants and the St. Louis Cardinals will play a regular season game at Rickwood Field, a nod to the history of the Negro Leagues, of players like Mays, Jackie Robinson, Monte Irvin, and Larry Doby, who integrated the Major Leagues, and in doing so, planted a small seed in the minds of those prior generations that all of us, regardless of our which team we root for, who we worship, or what skin color we have, saying, “Hey, we’re all more alike than we are different.”

The desegregation of Major League Baseball led to the desegregation of the military, of public schools, and of American society, and finally, MLB is acknowledging the contributions made by a generation of players who suffered unimaginably under Jim Crow laws and segregation.

That they – Willie, Jackie, Larry, Monte, Hank, Pumpsie, Elston, Frank, and so many more – are all gone now can only be attributed to the passage of time. The tragedy, of course, is not that they are gone, because we all will be one day, whether we want to think about it or not, regardless of how many games we played, homers we hit, widgets we made, columns we wrote, miles we drove, or whatever.

It’s that Major League Baseball waited far too long to acknowledge what they did for the game and for society, bringing us closer together, bridging an unimaginable divide by simply playing a game we all love.

When I was a child, my dad would occasionally pull out a small box of baseball cards, Topps and Bowman cards from the 1950s, the cardboard artifacts of his childhood purchased so long ago at Joe’s Candy Store on Union Turnpike in Queens and we’d look through them together.

There was a Sandy Koufax rookie card in that box, cards of Yogi Berra, Doby, Joe Black, and, of course, Willie Mays.

I’m now the age my dad was when he first took me to a Major League game, and when I look back at the players of my youth, there are few players I can point to who compare to Willie, who I never saw play.

Which, is to say, you don’t have to have a Ph.D. in statistics, you don’t have to look up comparable players on Baseball Reference, and you didn’t have to see Willie Mays play to know he was the greatest.

If you know baseball, you know, and you’ve known for a long time.