ORLANDO, Fla. – In Part One of World Baseball Network’s coverage from the Winter Meetings in Orlando, Jeff Kent finally got the call to Cooperstown as the lone player elected by the Contemporary Baseball Era Committee. Part Two examined how Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens fell short of the five-vote threshold, placing their Hall of Fame chances on a narrow path to a final review in 2031.

Part Three shifts the focus to the rest of a complicated ballot: Fernando Valenzuela, Carlos Delgado, Gary Sheffield, Don Mattingly, and Dale Murphy. Together, they represent the heart of the international and “borderline” cases the committee wrestled with in crafting the Class of 2026.

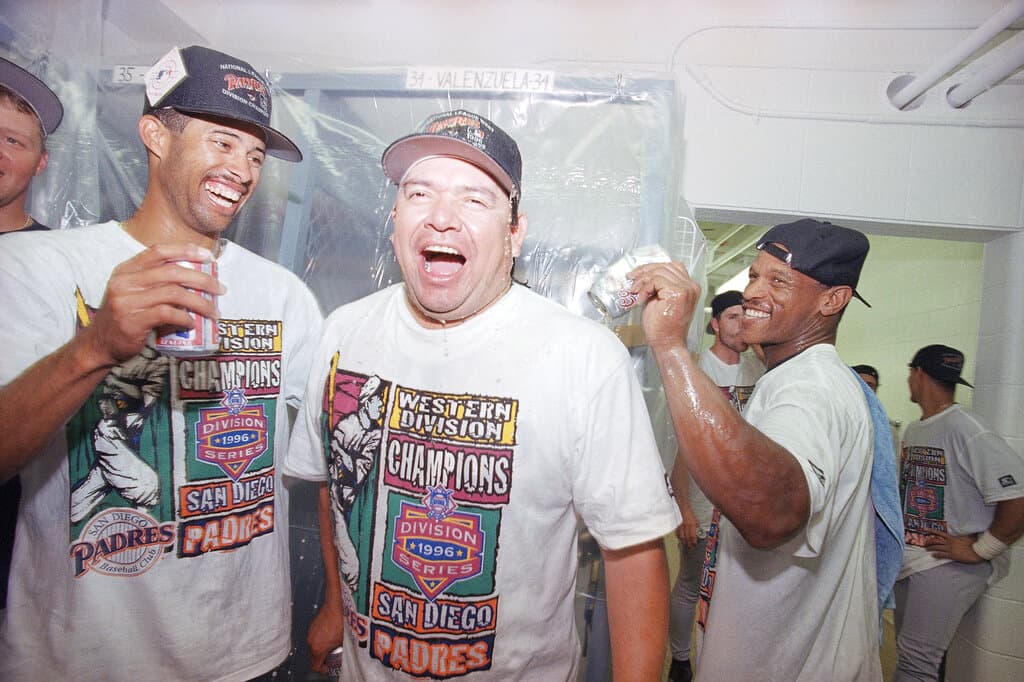

Valenzuela and Delgado were the two international-born stars on the ballot — Mexico and Puerto Rico, respectively — while Sheffield, Mattingly, and Murphy carried decades of offensive production, accolades, and long-running debates of their own. In the final tally, Delgado received nine votes, Mattingly and Murphy earned six each, and both Valenzuela and Sheffield finished with fewer than five, placing them alongside Bonds and Clemens in the group that will not return to the ballot in 2028.

Fernando Valenzuela’s case is not just about numbers. It is about a cultural shockwave that began in Mexico, rolled through Los Angeles, and helped knit together Mexican, Mexican-American, and U.S. baseball communities in a way no player had before.

On paper, his résumé is formidable. He was a six-time All-Star from 1981 to 1986, a World Series champion with the Dodgers in 1981, and the first player ever to win both the National League Cy Young Award and Rookie of the Year in the same season. He added a Gold Glove Award in 1986, two Silver Sluggers as a pitcher, led the league in wins in 1986, and topped Major League Baseball in strikeouts in 1981. He threw a no-hitter on June 29, 1990, and the Dodgers eventually retired his No. 34.

Valenzuela first appeared on the Baseball Hall of Fame ballot in 2003 and received just 6.3% of the vote, dropping off the BBWAA ballot the following year. More than two decades later, he resurfaced on the Contemporary Era Player Ballot in 2025, this time evaluated by a committee that had grown up watching Fernandomanía unfold in real time.

His journey started far from Dodger Stadium. In 1977, the left-hander from Sonora began his professional career with Mayos de Navojoa in the Liga Mexicana del Pacífico. A year later, he moved to the Guanajuato Tuzos of the Mexican Central League, going 5–6 with a 2.23 ERA. When the Mexican Central League was absorbed into the expanded Mexican League in 1979, Valenzuela’s 18-year-old arm suddenly found itself at the equivalent of Triple-A, and he responded with a 10–12 record, a 2.49 ERA, and 141 strikeouts for Leones de Yucatán.

The Dodgers found him almost by accident that same year, when scout Mike Brito traveled to Mexico to evaluate a shortstop named Ali Uscanga. Valenzuela fell behind Uscanga 3–0, then fired three straight strikes for the strikeout. By the end of that experience, the shortstop was secondary. Los Angeles purchased Valenzuela’s contract on July 6, 1979, for $120,000, with $20,000 going to Valenzuela and $100,000 to his club.

Two years later, Valenzuela exploded onto the U.S. stage. In 1981, at age 20, he led the majors in strikeouts, won the Cy Young and Rookie of the Year Awards, took home a Silver Slugger, and made his first All-Star team. He finished that regular season 13–7 with a 2.48 ERA in 25 starts, recording 11 complete games and eight shutouts while throwing 192.1 innings. He allowed 140 hits, 53 earned runs, and 11 home runs, walked 61 hitters, struck out 180, and posted a 1.045 WHIP.

Valenzuela carried that workload into October. In the 1981 World Series, he threw a complete game in his lone start, going nine innings, allowing nine hits and four earned runs, walking seven, and striking out six in a winning effort as the Dodgers defeated the New York Yankees.

Over a 17-year Major League career, Valenzuela pitched for the Dodgers from 1980–90, the California Angels in 1991, the Baltimore Orioles in 1993, the Philadelphia Phillies in 1994, the San Diego Padres from 1995–97, and the St. Louis Cardinals in 1997. He finished 173–153 with a 3.54 ERA in 453 appearances and 424 starts, throwing 2,930 innings, allowing 2,718 hits and 1,154 earned runs, and giving up 226 home runs. He walked 1,151 batters, struck out 2,074, and posted a 1.320 WHIP.

He remains the all-time leader in All-Star selections among Mexican-born players with six, ahead of Bobby Ávila’s three. Fittingly, his Hall of Fame honors already exist in the region that first embraced him: Valenzuela was inducted into the Mexico Baseball Hall of Fame in 2014 and the Serie del Caribe Hall of Fame in 2013.

His international résumé runs deeper than most U.S. fans realize. He pitched in the Caribbean Series in 1982 and 2001 with Naranjeros de Hermosillo and in 1993 with Venados de Mazatlán, posting a 1–0 record and a 1.05 ERA in four appearances. Across 25.2 innings, he allowed just three earned runs, 18 hits, and five walks while striking out 17. He also pitched for Charros de Jalisco in the Mexican League in 1992 and 1994, and for Águilas de Mexicali in the Liga ARCO Mexicana del Pacífico in 2006–07 and 2007–08.

Valenzuela received fewer than five votes from the Contemporary Era Committee in 2025, which means he will not be on the ballot in 2028. For many in Mexico and across Latin America, that gap between on-field impact, cultural legacy, and Hall recognition remains one of the most glaring disconnects in the modern voting structure.

If Valenzuela represents Mexico’s greatest pitching icon, Carlos Delgado stands as Puerto Rico’s modern power benchmark.

Delgado’s career included two All-Star selections, three Silver Slugger Awards, the 2000 AL Hank Aaron Award, the 2006 Roberto Clemente Award, and an AL RBI crown in 2003. On September 25, 2003, he famously hit four home runs in one game. He has been honored on the Toronto Blue Jays Level of Excellence, and in 2015 he was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. For many fans, Fernando Alvarez puts it best.

That same year, Delgado received just 3.8% of the vote in his first appearance on the BBWAA Hall of Fame ballot, falling below the 5% threshold needed to remain eligible. A decade later, he resurfaced on the Contemporary Baseball Era Committee ballot in November 2025—and this time, his support was far stronger. Delgado finished second on the ballot with nine votes, trailing only Kent.

Delgado’s international record is central to his candidacy. He played for Puerto Rico in both the 2006 and 2009 World Baseball Classics. In 2006, he recorded one hit in his lone at-bat as Puerto Rico went 3–0 in Pool C at Hiram Bithorn Stadium, only to be eliminated at 1–2 in the second round on home soil. In 2009, Delgado appeared in six games and slashed .438/.625/.938 over 16 at-bats, with four runs scored, seven hits, two doubles, two home runs, five RBIs, seven walks, three strikeouts, and a stolen base, as Puerto Rico again rolled to a 3–0 mark in pool play.

After his playing days, Delgado served as the hitting coach for Puerto Rico’s national team in the 2013 and 2017 World Baseball Classics. Puerto Rico reached the final in both tournaments, losing to the Dominican Republic in San Francisco in 2013 and to the United States at Dodger Stadium in 2017.

Delgado has the most home runs by a Puerto Rican-born player in MLB history, with 473. Long before that milestone, he was the starting catcher for the legendary 1994–95 Senadores de San Juan “Dream Team,” which featured Hall of Famers Roberto Alomar and Edgar Martínez alongside Rey Sánchez, Ricky Bones, Bernie Williams, Carlos Baerga, Rubén Sierra, and Juan González. That squad went 6–0 at the 1995 Caribbean Series at Hiram Bithorn Stadium, and Delgado was selected to the All–Caribbean Series team.

In the majors, Delgado played 17 seasons with the Toronto Blue Jays from 1993–2004, the Florida Marlins in 2005, and the New York Mets from 2006–09. He appeared in 2,035 games and produced a 44.4 WAR over 8,657 plate appearances, with 2,038 hits, 483 doubles, 18 triples, 1,512 RBIs, 14 stolen bases, 1,109 walks, 1,745 strikeouts, and a .929 OPS.

Delgado’s nine votes in this cycle suggest he could enter the 2028 committee meeting as one of the leading international candidates, even as other big names cycle out.

Gary Sheffield’s career spanned 22 seasons and nine franchises, with numbers that would, in another era, make him a Hall of Fame lock. He was a nine-time All-Star, a 1997 World Series champion with the Florida Marlins, a five-time Silver Slugger, and the 1992 National League batting champion.

Sheffield’s international profile took shape early. At 11 years old, he played for the Belmont Heights Little League All-Stars, a team that reached the finals of the 1980 Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pa., before losing 4–3 to Taiwan. Sheffield set a doubles record at that LLWS that stood until 2012.

By his senior year at Hillsborough High School in Tampa, Fla., Sheffield was on every scout’s radar. He hit .500 with 15 home runs in 62 official at-bats and was named the Gatorade National Player of the Year before being selected sixth overall in the 1986 MLB Draft by the Milwaukee Brewers.

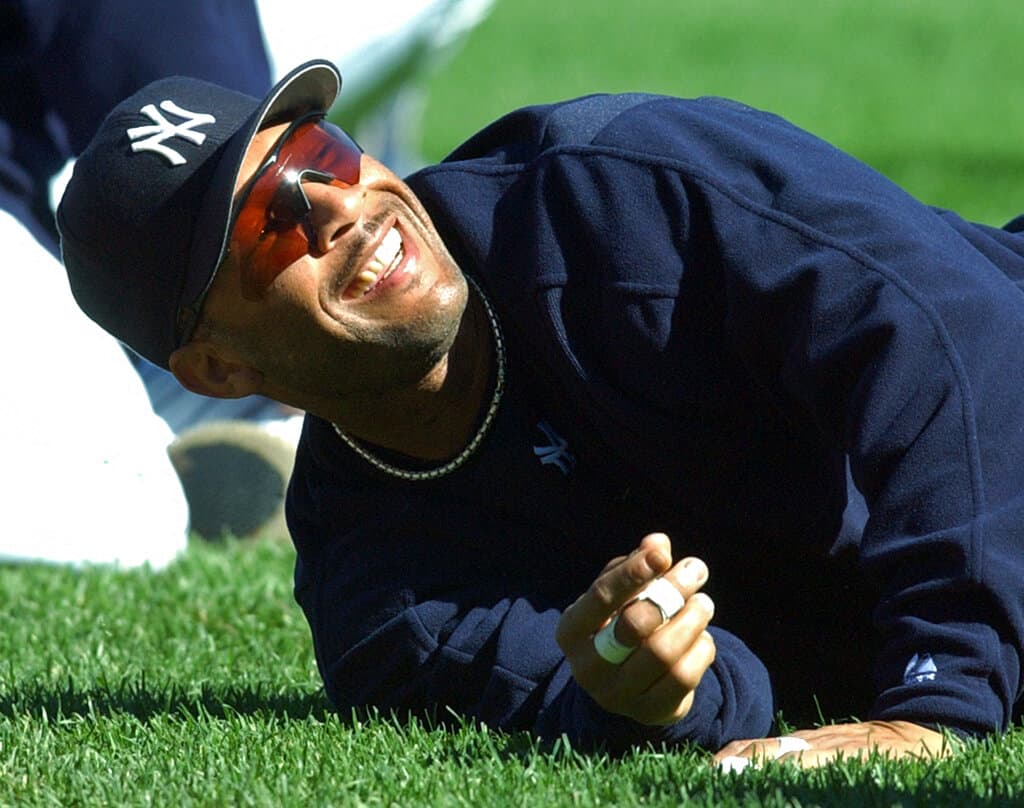

New York Yankees’ Gary Sheffield smiles as he stretches Monday, Oct. 11, 2004 at Yankee Stadium in New York. The Yankees will play the Boston Red Sox in the American League Championship Series beginning Tuesday. (AP Photo/Bill Kostroun)

Sheffield would go on to hit 509 home runs and drive in 1,676 runs in the majors, playing for Milwaukee from 1988–91, San Diego from 1992–93, Florida from 1993–98, the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1998–2001, the Atlanta Braves from 2002–03, the New York Yankees from 2004–06, the Detroit Tigers from 2007–08, and the New York Mets in 2009. He topped 300 total bases six times and had eight seasons with at least 100 RBIs, splitting time between third base and the outfield.

Sheffield first appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot in 2015, drawing 11.7% of the vote—enough to remain eligible but well short of the required 75%. In 2024, his tenth and final BBWAA ballot, Sheffield climbed to 63.9%, but still fell short.

Like Bonds and Clemens, his candidacy has been shadowed by PED allegations. In his book Inside Power, Sheffield wrote that he was given a cream by a trainer during a workout with Bonds in 2001 to help heal his knee after surgery, and that he did not know it contained steroids. He has maintained the cream did nothing to improve his performance, pointing to his numbers after that period. Sheffield’s name appeared in the Mitchell Report in 2007 as a player who had obtained and used steroids. He agreed to speak with investigators, but the interview never took place before the report was published. In Game of Shadows, reporters Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams alleged that Sheffield had received steroids from trainer Greg Anderson, and cited steroid calendars outlining alleged cycles.

Over 22 seasons, Sheffield played in 2,576 games and posted a 60.5 WAR with a .292 batting average over 10,947 plate appearances. He recorded 2,689 hits, 467 doubles, 27 triples, 509 home runs, 1,676 RBIs, 253 stolen bases, 1,475 walks, 1,171 strikeouts, and a .907 OPS.

In this ballot cycle, Sheffield joined Bonds, Clemens, and Valenzuela among those who failed to reach the five-vote threshold, ensuring he will not be considered again in 2028.

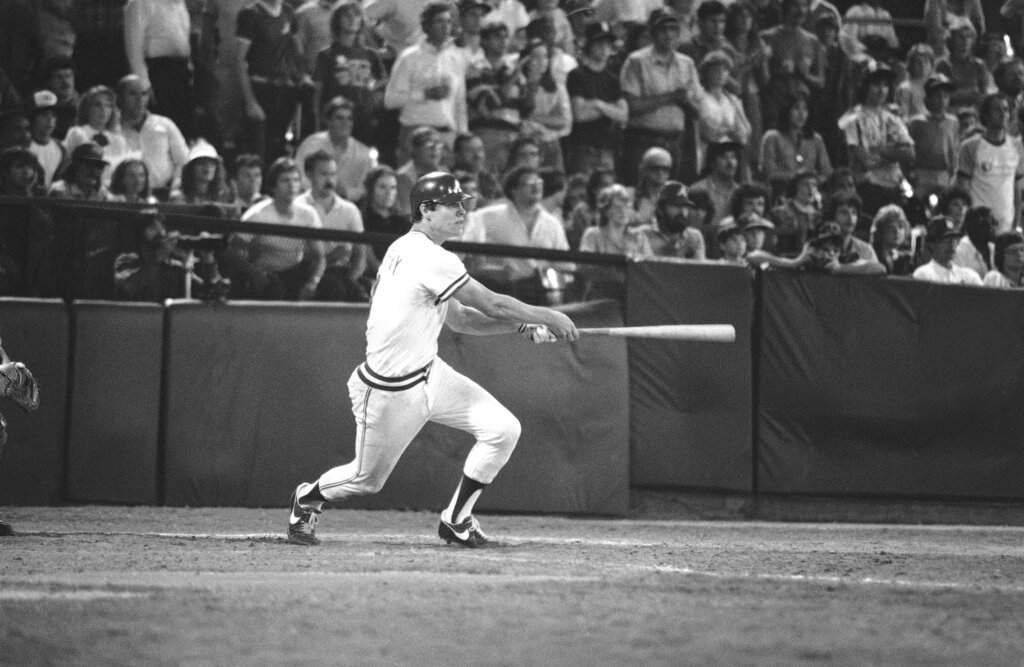

Don Mattingly and Dale Murphy entered this cycle as two of the most frequently debated “almost” candidates of the last four decades. Both have iconic status within their franchises. Both have long lists of accolades. Both finished with six votes from the committee in Orlando—respectable support, but short of the 12 required for enshrinement.

Mattingly, a six-time All-Star, 1985 AL MVP, nine-time Gold Glove winner at first base, three-time Silver Slugger, batting champion, and RBI leader, has long been viewed as a peak-value candidate whose prime was cut short by back injuries. Selected by the New York Yankees in the 19th round of the 1979 Draft, he emerged from Reitz Memorial High School in Evansville, Ind., where he hit .463 and helped the program go 94–9–1 over four seasons. He still holds school records for hits, doubles, triples, RBIs, and runs scored, and his 25 triples stood as an Indiana state record.

Los Angeles Dodgers’ Tommy Lasorda, left, and manager Don Mattingly smile as they talk to each others before the Dodgers’ spring training baseball game against the Milwaukee Brewers on Saturday, March 19, 2011, in Glendale, Ariz. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh)

Mattingly became eligible for the Hall of Fame in 2001, receiving 28.2% of the vote before sliding to 20% the following year. Over the next decade, he generally hovered between 10% and 14%, finishing at 9% in 2015, his final year of BBWAA eligibility after the Hall reduced the eligibility window to ten years. In 14 seasons with the Yankees, Mattingly played in 1,785 games and produced a 42.4 WAR across 7,722 plate appearances, with 2,153 hits, 442 doubles, 20 triples, 222 home runs, 1,099 RBIs, 14 stolen bases, 588 walks, 444 strikeouts, and an .830 OPS. His uniform No. 23 is retired by the Yankees, and he is honored in Monument Park.

Murphy, meanwhile, was one of the defining players of the 1980s. A seven-time All-Star and two-time NL MVP, he won five Gold Gloves in center field and four Silver Slugger Awards, along with two home run titles and two RBI crowns. His No. 3 is retired by the Atlanta Braves, and he is a member of the Braves Hall of Fame.

At the time of his retirement, Murphy’s 398 home runs ranked sixth in National League history among right-handed hitters, and his 202 home runs as a center fielder ranked ninth in Major League history. His .469 slugging percentage was the fifth highest among NL players with at least 1,000 games in center field. With Atlanta, he set franchise records for games, at-bats, hits, RBIs, runs, doubles, walks, and total bases, many of which were later surpassed by Chipper Jones.

The six votes each received in Orlando show that both Mattingly and Murphy still command respect in the committee room, but they remain outside the plaque gallery, at the mercy of future ballots and shifting committee composition.

Taken together, Valenzuela and Delgado represent the expanding international front of Hall of Fame debates. One has already been immortalized in Mexico and the Caribbean, but not yet in Cooperstown. The other, Puerto Rico’s all-time home run leader, has gone from 3.8% on a BBWAA ballot to second place on a Contemporary Era ballot in a decade.

Sheffield, Mattingly, and Murphy, meanwhile, highlight how awards, milestones, and era context collide with evolving standards, PED scrutiny, and positional value metrics.

From here, Delgado, Mattingly, and Murphy remain eligible for nomination when the committee reconvenes in 2028, with Delgado’s nine votes making him a particularly strong candidate to resurface. Valenzuela, Sheffield, Bonds, and Clemens will have to wait until 2031 for what may be their final review.

With Kent heading to Cooperstown, Bonds and Clemens pushed to the brink, and a new wave of international stars moving closer to the plaque room, the Contemporary Era ballot has made one thing clear in Orlando: the Hall of Fame is no longer just a referendum on numbers. It is a running argument about what kind of story baseball wants to tell the world.

World Baseball Network will continue to follow that story as the BBWAA prepares to announce its own voting results in January and as the next generation of international stars takes aim at Cooperstown from leagues and tournaments across the globe.

Photo: Los Angeles Dodgers rookie pitching sensation Fernando Valenzuela autographs baseballs for a group of teachers from St. Joseph’s Catholic School in Placentisa Cal. on May 31, 1981 before game against the Cincinnati Reds in Los Angles. (AP Photo/Ramussen)