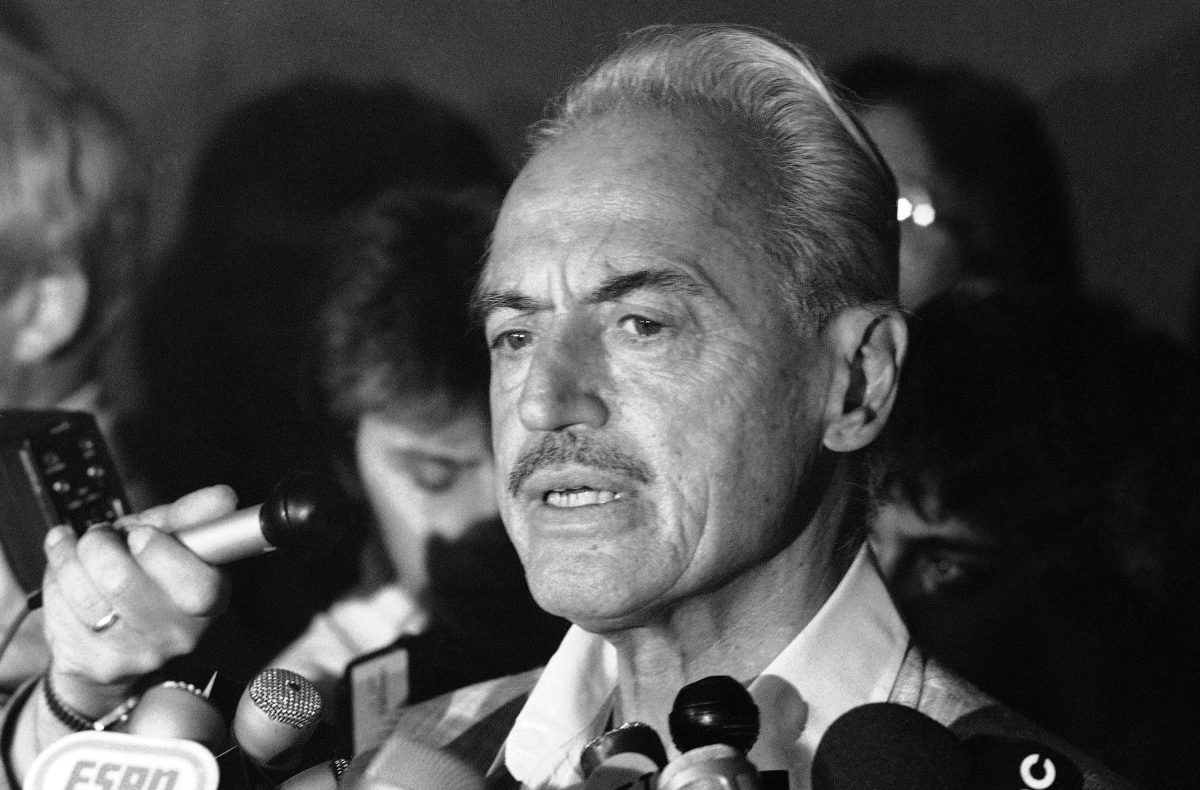

Countless figures in Major League Baseball’s illustrious past have molded my understanding of how the game should be honored and enjoyed. Much like musical giants—Prince, Elvis, Dolly, Shania, Michael, Sinatra—whose names echo with ease, baseball’s heroes command deep respect: Jackie, Babe, Hank, Reggie, Brooks, Sandy, Stan-the-Man, Joe D, Mickey, Yogi, Ichiro, Pedro, Chipper, Big Papi, Jeter, Ohtani. In no other sport do managers wear the team’s uniform, their legacies enshrined in history: Alston, Sparky, Durocher, Stengel, Torre, La Russa. Among these luminaries stands Dorrel Norman Elvert “Whitey” Herzog, a trailblazer who grasped baseball’s spirit through instinct rather than mere statistics.

Whitey Herzog: The Master of Intuition

Whitey Herzog’s time as an MLB player was unassuming—a .257 average with 25 home runs—but his true talent emerged in team management. His career path reflects his impact:

1964 to 1970: he served as the Mets’ Director of Player Development, laying the groundwork for the 1969 Miracle Mets’ World Series victory and the 1973 NL pennant.

1975 to 1979: he managed the Royals to three consecutive AL West titles, only to be halted by George Steinbrenner’s Yankees.

1980 to 1990: he led the Cardinals to the 1982 World Series title and three NL pennants.

Herzog’s “Whitey-ball” approach—built on speed, pitching, and defense—highlighted National League innovation. He rejected the early, primitive versions of modern analytics, instead trusting his instincts and scouting acumen. A sportswriter—not the Red Sox’s Johnny Pesky—reportedly gave Herzog his “Whitey” nickname, linking his blonde hair to Yankees pitcher Bob Kuzava, dubbed “The White Rat.” Pesky, known for Fenway’s Pesky Pole, later supported the nickname, which became widely embraced in baseball circles.

This was Whiteyball #ForTheLou pic.twitter.com/hREYLQQJD7

— John Hough (@JohnHough__) April 16, 2024

Self-effacing, Herzog quipped: “Baseball has been good to me since I quit trying to play it.”

His philosophy was simple: “Be on time. Bust your butt. Have some laughs while you’re at it.”

On managing pitchers: “We need three kinds of pitching: left-handed, right-handed, and relief… If you don’t have outstanding relief pitching, you might as well piss on the fire and call the dogs.”

Analytics vs. Intuition: A Pendulum Overswung?

In its earlier days, baseball flourished through instinctive choices, but now, data reigns supreme, propelled by Ivy League-educated general managers—40% of whom graduated from top-tier schools like Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. The Moneyball movement, ignited by Billy Beane in 2003 and shaped by Dartmouth’s Sandy Alderson, marked the rise of a data-centric approach. Sophisticated metrics such as bWAR, exit velocity, and defensive alignments have reduced the influence of instinct, steering decisions in ways that may overlook the value of gut feel.

This data-driven mindset echoes a legal divide: originalist justices or traditionalists who interpret laws strictly in adherence to statutory intent versus living document counterparts who view the Constitution as adaptable to evolving circumstances. In baseball, while statistics bring accuracy, it’s instinct that imbues the game with spirit—only their coexistence can safeguard its heart.

In my work in commercial real estate (CRE), we assess metrics like NOI and ROI to guide decisions, but closing a deal relies on instinct, trust, and follow-through. Baseball’s current path resembles Wall Street’s reliance on algorithmic ETFs, often clouding the game’s inherent simplicity.

Understanding bWAR: Value or Veil?

Wins Above Replacement (WAR) quantifies a player’s worth by comparing their performance to that of a replacement-level athlete—essentially the gap between a standout and a typical minor league call-up or bench player. Baseball-Reference’s bWAR accounts for league differences, historical context, and ballpark factors, distinct from FanGraphs’ fWAR, which employs a different formula for assessing a player’s seasonal impact.

Top-tier players often post a bWAR of 8.0 or above, ranking them among the game’s all-time elites. Here are some remarkable examples:

Babe Ruth in 1923 with a 14.1 bWAR

Brooks Robinson in 1964 at 8.4 bWAR

Aaron Judge in 2024 with 11.1 bWAR

Judge again in 2025 (~59 games as of 6/1/2025) at ~4.5 bWAR, on pace for ~13.0 bWAR

Mike Trout in 2012 with 10.5 bWAR

Pitchers are evaluated similarly, with elite seasons also starting at the 8.0 bWAR threshold. These legendary campaigns redefined dominance on the mound:

Pedro Martínez (1999) – 9.7 bWAR

Sandy Koufax (1965) – 8.1 bWAR

Bob Gibson (1968) – 11.9 bWAR

Greg Maddux (1995) – 9.6 bWAR

Randy Johnson (2002) – 10.7 bWAR

At present, Detroit’s Tarik Skubal sits at 3.9 bWAR with a 2.39 ERA and a strikeout pace of 230–240 Ks. If he reaches 180–190 innings, he could finish with a bWAR between 9.3 and 9.8—placing him alongside the most dominant pitchers in MLB history.

bWAR can forecast team victories with roughly 85% accuracy, akin to how debt yield in commercial real estate underwriting gauges financial health.

Still, as Whitey Herzog reminded us: “You don’t need a lot of statistics to know when a guy is playing well.”

The Modern Crisis: Data Over Heart?

While analytics uncover talent, they risk turning baseball into a predictable formula.

Judge’s projected ~12.6 bWAR is impressive, yet it fails to capture his larger-than-life, Ruth-like presence. On-field choices—like pitcher matchups and defensive shifts—now depend heavily on data, often sidelining instinct.

A 2021 SABR study revealed that clutch moments, such as Derek Jeter’s iconic 2001 ALDS flip play to catch Jeremy Giambi at the plate, often escape statistical analysis. That play—marked by cunning, positioning, and execution—shaped Jeter’s Hall of Fame legacy, not a measurable metric.

Can you picture legends like Sparky Anderson, Earl Weaver, or Tommy Lasorda managing through spreadsheets? This data-first mindset, echoing the legal clash between strict originalists and the living document judicial split, endangers baseball’s spirit. A balanced approach is essential.

Free Agency’s Revolution: Flood, Miller, and Money

Baseball’s economics shifted through Curt Flood and Marvin Miller, freedom fighters who toppled the reserve clause.

Key events:

1969–1972: Flood, traded against his will, sued MLB with Miller’s backing, declaring: “I do not regard myself as a piece of property to be bought and sold.” Though losing in court, his stand sparked reform.

1975: The Seitz Decision freed pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, ending indefinite contract renewals. MLB fired arbitrator Peter Seitz, but free agency was born.

Miller’s negotiations didn’t just skyrocket salaries—they reshaped the entire process. What began as a fundamental player-rights movement has evolved into a system where clubs must now pay a king’s ransom for elite talent.

Today, only a handful of teams spend aggressively:

Dodgers (Guggenheim) and—in addition to Juan Soto—the soon-to-be Mets (Point 72) dominate the market.

Astros (Crane Capital) and Orioles (Carlyle Group) have yet to match that aggression.

Even if George Steinbrenner were alive, competing at today’s financial scale—despite the Yankees’ top payroll—would be a challenge, perhaps.

Meanwhile, small-market champions like the 2019 Nationals, 2016 Cubs, and 2015 Royals all saw their rosters dismantled as financial constraints forced stars out.

Now, in 2025, the Detroit Tigers—a scrappy squad under AJ Hinch, led by ace Tarik Skubal on a one-year deal—seek a small-market miracle.

With Skubal’s dominance (2.26 ERA, 99 strikeouts over 75.2 innings), he’s on pace for approximately 246 strikeouts this season, positioning him as a leading Cy Young contender. Detroit could join the ranks of the 2015 Royals or 2019 Nationals—but their window is extremely narrow.

The Dodgers, wielding a blank check, could loom as Skubal’s likely suitor in 2026, threatening to end Detroit’s dream—if the ace is denied his Motor City bag, as it were.

As Whitey Herzog put it: “There’s not any way to build a team today. It’s just how much money you want to spend.”

The Power Shift: Billionaire Owners and Millionaire Players

The financial landscape of baseball has evolved into a game of titans, where multibillionaire owners and multimillionaire players both navigate the system Miller helped forge and Flood sacrificed.

Despite salary caps, luxury tax penalties, and revenue-sharing mechanisms, top-tier clubs can still spend aggressively, leveraging vast media deals, franchise valuations, and ownership portfolios beyond just baseball. Teams like the Dodgers (Guggenheim) and Mets (Point 72—Steve Cohen) have owners with deep financial reservoirs, allowing them to treat payroll as an investment rather than a burden.

Meanwhile, players—from Ohtani to Soto—command generational wealth, yet their ability to negotiate freely stems directly from Miller’s fight to end contract servitude and Flood’s bold stand against MLB’s reserve clause.

Even today, Miller and Flood’s legacies are evident in how free agency dictates competitive balance. What once freed players from club control now presents a new challenge—the pendulum has swung, forcing smaller-market teams into a cycle of talent churn, while financial juggernauts absorb the game’s elite.

A hat tip to Miller and Flood is more than justified—both sides of the equation have benefited from their work. The question remains: Has the system truly balanced the scales, or has leverage simply transferred from one power structure (ownership) to another (player elite)?

Restoring the Soul: A Call for Balance

Baseball isn’t spreadsheets or TV contracts—it’s a sandlot game of heart, hustle, and triumph.

We measured greatness by moments, not WAR. Today, Ivy League-driven analytics, free agency churn, and big-market dominance threaten its soul.

Why should only the Dodgers—and now the Mets—wield open checkbooks? Few other teams can afford blank checks like these two franchises. These days, the Bronx Bombers are even being more selective—but who else?

In the 1970s, during my adolescence, stars spent most of their careers with clubs, weaving community ties. Fans built lifelong connections, knowing their heroes—on balance—wouldn’t up and leave.

But today’s free agency model has fractured that bond. Homegrown stars rarely remain, leaving small-market franchises unable to retain the talent they develop. Even championship teams like the 2019 Nationals or 2025 Tigers—should they win it all—face inevitable dismantling.

How can a young fan stay loyal when the player they idolize is gone by the next contract cycle? The revolving door of talent strips franchises of identity and erodes the generational ties that made baseball timeless.

Baseball was never just a business model. If free agency dominance and analytics obsession continue, what truly remains? Will the next generation inherit legends, or just spreadsheets?

The balance of power in baseball didn’t shift overnight. It took the defiance of figures like Curt Flood, who challenged the reserve clause, and Marvin Miller, who engineered free agency, to reshape the game’s economic landscape. But at what cost?

Marvin Miller, whose work reshaped Major League Baseball and player rights, was finally inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2019—a long-overdue recognition for arguably the finest labor union lawyer in sports history. His election via the Modern Baseball Era Committee cemented his role as a transformative figure, ensuring his name stands alongside the players whose careers he revolutionized.

Curt Flood, meanwhile, was more than just a conscience-driven trailblazer—he was a legitimate star. A former Phillie and Cardinal, Flood was a three-time All-Star, a two-time World Series champion, and a seven-time Gold Glove winner in center field. His fight against baseball’s reserve clause wasn’t just symbolic—it came at the cost of an accomplished career that should have lasted longer.

In memory of Whitey Herzog, Vin Scully’s poetry on the mic, and for every kid with a bat and a glove, let’s blend diamond wisdom with data, ensuring baseball remains a game of passion—affordable, timeless, and true—so legends like Herzog may rest assured knowing the game hasn’t sold itself. If you missed it, read Reginald Armstrong’s Memorial Day column, “Restoring the Integrity of America’s Pastime”.