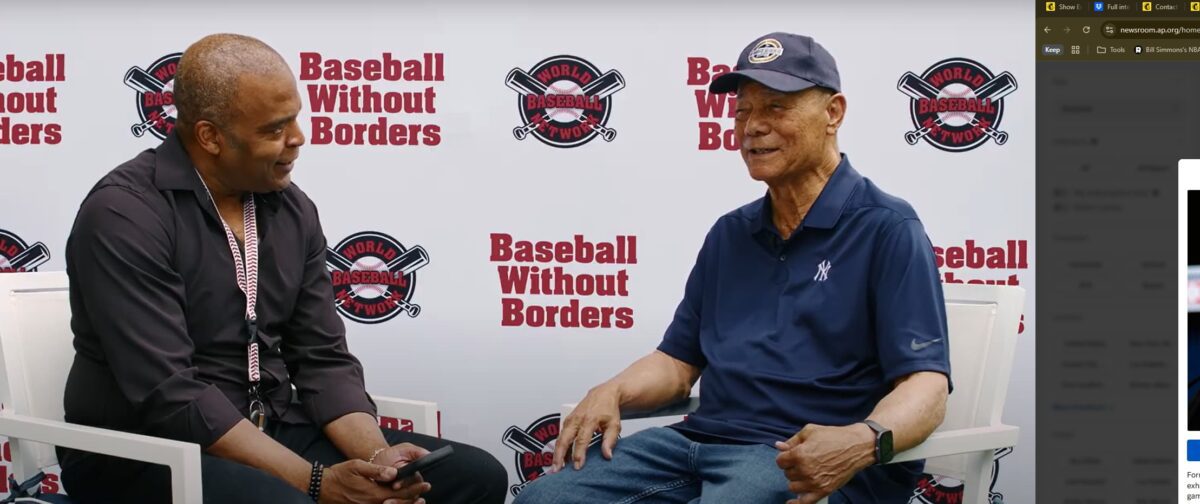

At a recent event hosted by the Nick Loeb Foundation, New York Yankees legend Roy White sat down with World Baseball Network’s Reginald Armstrong for a wide-ranging conversation on leadership, legacy, and what it means to wear the pinstripes with purpose.

Now 80, White remains a quiet pillar in Yankees history. A two-time World Series champion and lifelong Yankee, he spent all 15 seasons of his Major League career in the Bronx — a rarity in any era. At the Nick Loeb Foundation event, White opened up about his experience witnessing some of the most unforgettable moments in baseball history, including Reggie Jackson’s three-homer night in Game 6 of the 1977 World Series.

“I was on the bench — I wasn’t playing in that game,” White said. “But what Reggie did… nobody had ever done that before. Three home runs. Three different pitchers. Three consecutive pitches. That was Reggie. When the game was on TV, we always said, ‘Reggie’s gonna hit one.’”

That performance, which clinched the Yankees’ 21st championship, helped solidify Jackson’s legend. But for White, the moment wasn’t just about the spotlight — it was a culmination of a team reclaiming its identity after a humiliating sweep by the Reds in 1976.

“It wasn’t payback — ‘cause it wasn’t the Reds — but it was the Dodgers,” White said. “And I grew up watching Dodgers-Yankees World Series. It was special.”

White’s humility stood in contrast to the bombast of Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, whom he described as “kind of a Jekyll and Hyde.” But he made one thing clear: “There’s no doubt we wouldn’t have achieved what we did without George. I was there during the CBS era — we didn’t bring in good players. George changed that.”

White’s tenure also bridged generations, from Mickey Mantle to Thurman Munson to Reggie Jackson. His memories of Mantle remain vivid — walking into the Yankee Stadium clubhouse for the first time and seeing his childhood idol in the corner. “I’d watched him in Little League. Never thought I’d be a Yankee myself.”

But it was Munson who left the deepest emotional impact. White, who sat next to the late Yankees captain in the clubhouse for a decade, recalled the day Munson died. “He wanted to be a pilot so he could fly home after Sunday doubleheaders and be with his family. That’s what motivated him,” White said, holding back emotion. “He had a tough exterior with the press, but he was a soft-hearted, good guy. A family man.”

When asked what grounded him through the pressure of New York, White spoke of his upbringing. Born to a Black mother and a German father, he didn’t fully understand the complexities of race until his teenage years in Los Angeles and Compton. “Being kind of in the middle always made me low key. I respected all points of view,” he said. “I knew to stay in the majors, the manager had to like me. So I learned how to bunt, hit behind the runner — do everything.”

Today, White’s focus remains on giving back. His Roy White Foundation helps students pay for college and now also supports children on the autism spectrum, inspired by his grandson. Donations can be made at RoyWhiteFoundation.com.

“I still hear from people who say I was one of their favorite players — that I played hard and that I was a gentleman,” White said. “That’s always rewarding.”

As a token of appreciation, World Baseball Network presented White with a custom challenge coin engraved with “Baseball Without Borders.”

“I’ll put this in my office,” White said. “Right next to all my memorabilia.”

Reginald Armstrong: Through Munson’s last chapter and Reggie’s rise — through chaos, championships, and change — he was grace in a pinstriped storm. I present to you Roy White. Roy, thank you for being here.

Roy White: Great to be here with you.

Reginald: Rich. We’re gonna go right into it. Game 6, 1977. My namesake — Reggie. Reggie Jackson. Three home runs on three consecutive pitches, off three different pitchers: Burt Hooton in the fourth, Elias Sosa, and then Charlie Hough in the eighth. Now, I wasn’t there, but it’s my understanding that before the game, Jolting Joe DiMaggio — the Yankee Clipper — sat beside Reggie in the clubhouse and told him what Reggie already knew: that he was a great player. This was before dazzling the world with that Mr. October performance and the Yankees’ 21st championship. Did you sense in that moment, before, during, or after, that you were witnessing something immortal?

Roy White: Oh, no doubt. I was on the bench — I wasn’t playing in that game. That was something nobody had ever done — three home runs in a World Series game, off three different pitchers, on three consecutive pitches. It was pretty amazing. And Reggie was that type of guy. When the game was on TV, we always said, “Reggie’s gonna hit a home run,” because he could rise to those kinds of occasions. So it wasn’t a surprise that Reggie could do something like that.

Reginald: And to clinch it all.

Roy: Yes, definitely.

Reginald: What do you remember most about the atmosphere, the team, and the way that night unfolded?

Roy: We knew we were going to win. We got beat by the Cincinnati Reds in ’76, so we wanted to get back and show the world — or at least baseball fans in America — that we had a good team and could win a World Series. Getting swept by Cincinnati was embarrassing. It wasn’t payback — ’cause it wasn’t the Reds — but it was the Dodgers. And I grew up watching Dodgers vs. Yankees in the World Series. So that made it special.

Reginald: You saw the many shades of The Boss, George Steinbrenner. What was it like navigating his intensity, his loyalty, and his unpredictability?

Roy: I didn’t have much contact with him as a player. I never had any personal conversations, and he never criticized me in the press. But I got to know him better when I became a coach and worked in the front office. George was kind of a Jekyll and Hyde — your best friend one moment, then wouldn’t talk to you the next. But one thing’s for sure: we wouldn’t have achieved what we did without him taking over the Yankees. I was there during the CBS era — we didn’t bring in good new players, and we had losing teams for a long time. When George came in, that changed. He wasn’t afraid to spend money and bring in guys who could help.

Reginald: And he wasn’t afraid to be the face of the franchise either.

Roy: That’s right — he was not.

Reginald: Mickey Mantle. What did you glean from him — not just as a teammate, but in presence and silence?

Roy: That was one of my greatest thrills. The first time I came into the Yankee Stadium locker room, I looked down in the far-right corner, and there was Mickey Mantle. I’d watched him as a kid in Little League and Babe Ruth League — him, Whitey Ford, Roger Maris. I had no idea I’d ever be in the Yankee clubhouse, much less be a Yankee. They weren’t even my favorite team growing up. It was crazy — and really special. The thing I’m most proud of is that I was a lifetime Yankee — 15 years with one team. Only a few of us can say that.

Reginald: And as a man of color at that time, for that organization.

Roy: That’s true.

Reginald: The old Yankee Stadium had ghosts, echoes, and a pulse. What can’t be recreated in the current stadium?

Roy: It’s not the same. I wish I’d had a chance to play in today’s Yankee Stadium — I think I’d have better numbers. The original had “Death Valley” out in left-center and center field. You’d lose 20 or 30 home runs over your career. I always say Mickey Mantle might’ve hit 800 home runs in today’s ballpark. He and Joe D lost hundreds of balls out there. I caught a lot — over 400 feet out. The stadium was unique — the wall escalated up as it moved toward center. Short down the lines — 301 to left, 296 to right — but then it opened up: 402, 415, 457, 463. Right-center was about 385. First time I ran out there, I looked back to home plate and felt like I needed binoculars. It was so far — I thought I was going to lose my breath! I said, “How can anyone hit a ball that far?”

Reginald: What are you most proud of — not just on the field, but in how you carried yourself through eras of change?

Roy: The toughest thing is being able to come to New York and perform well. There’s more pressure and scrutiny than anywhere else in the Majors. To be able to handle that and play on two championship teams — that was special. And to play with legends like Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, Roger Maris, Elston Howard, Bobby Richardson — tremendous guys. Then later on: Thurman Munson, Reggie, Chris Chambliss, Mickey Rivers, Ron Guidry, Catfish Hunter — just a great group of players.

Reginald: Since you mentioned Thurman — would you share a thought on that tragedy?

Roy: Thurman was special from day one. He came into the clubhouse as a rookie and sat next to me for 10 years. First game — someone tried to steal second, and I didn’t even see the ball come out of his hand. He had the fastest release I’ve ever seen. He threw the guy out by 10 feet and had a base hit, too. He belonged right away. We became close friends. After games, he’d always ask me where to eat — I was the Yankees’ gourmet. I knew the best restaurants in the American League. We flew together a lot, and later on, he started studying flight manuals next to me. He really wanted to be a pilot. It was crushing to lose him. I was that close to him — it hit hard. He had a tough exterior with the press, but he was really soft-hearted and a family man. That’s why he bought the plane — so after Sunday doubleheaders, he could fly home to be with his family and return for Tuesday’s game.

Reginald: I believe you played that Monday night game on ABC, right?

Roy: Yeah — that night. Cosell. They did the dedication. That was something else.

Reginald: What grounded you through the spotlight and pressure?

Roy: I came from a mixed marriage — my mom was Black, my dad was of German descent. I didn’t realize what that meant until I got older, living in L.A., and then Compton. That shaped me. Being kind of in the middle made me more low-key — I respected all points of view. People always thought I was older than I was — I was mature for my age. When I got to the Majors, I told myself: to stay, the manager has to like me. So I made sure I could do everything — bunt, hit and run, move runners. I wanted to be proficient in all areas so I could stick around.

Reginald: And you did. You stuck around a long time. What do you miss most — not just the uniform, but the heartbeat?

Roy: Just being able to perform in front of New York fans. To this day, people come up and tell me I was one of their favorite players — that they liked how I played, that I played hard and was a gentleman. That’s rewarding to hear.

Reginald: You’ve seen the game across eras — from Mantle to Mattingly. What’s missing from the game today?

Roy: More contact at the plate. We’re in a home run era — everyone’s swinging for the fences with launch-angle swings. Too many strikeouts. Not enough guys choking up with two strikes and trying to put the ball in play. You need base runners. Right now, there are games with 25 strikeouts and nothing happening. That’s what’s missing.

Reginald: I couldn’t agree with you more.

Roy: Yeah.

Reginald: From championships in the Bronx to leadership on and off the diamond — you’ve always carried yourself with dignity. What are you focused on today? And how can people support you?

Roy: I have the Roy White Foundation. Our mission is to help kids go to college — give them some financial aid. We’ve also added autism to the mission — my grandson is on the spectrum. You can donate online at RoyWhiteFoundation.com. We help kids go to college, and help kids on the autism spectrum.

Reginald: Excellent. Your consistency and quiet strength remain a model. Thank you for your voice, your grace, and for sharing it with us here at the World Baseball Network. I’ve got something for you — on behalf of WBN, a challenge coin. It says Baseball Without Borders. Enjoy that, sir.

Roy White: I will put this in my office — next to all my memorabilia.