Of the countless packs of 1986 Topps baseball cards I purchased at the Gourmet Deli and Rite-Aid Pharmacy and Acme and Wawa and, well, anywhere that sold them, there was one card I wanted and needed for a long time to complete the set of 792.

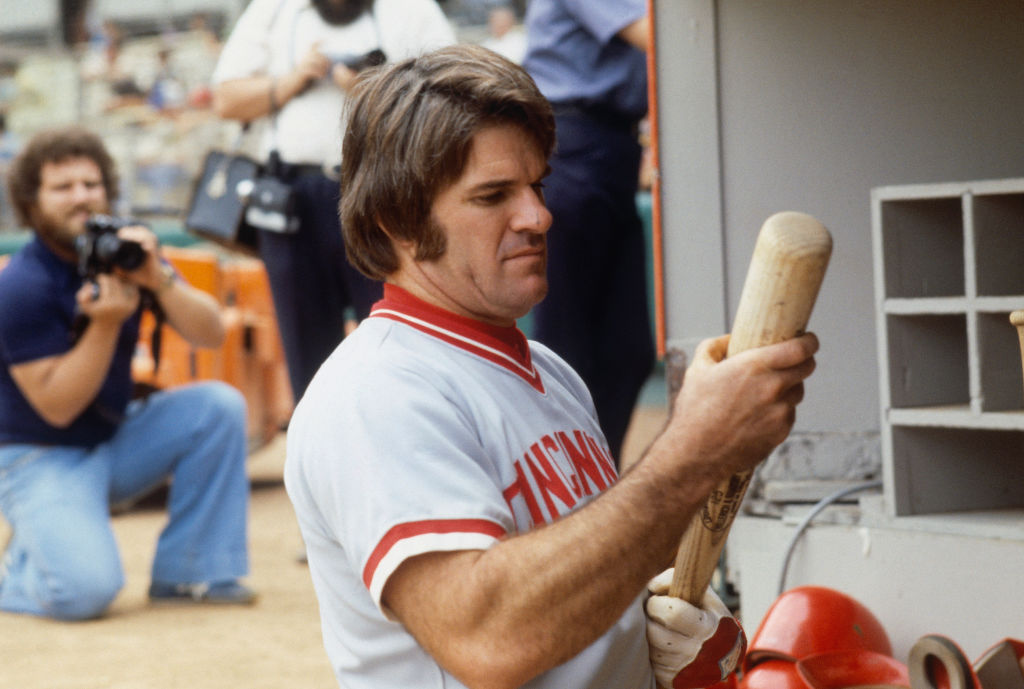

It was card No. 1, which featured Cincinnati Reds player/manager Peter Edward Rose, who died Monday at age 83, clad in a road grey Cincinnati Reds uniform, time stopped in the batter’s box of Shea Stadium, watching what can be assumed was yet another base hit.

He was an easy choice to be No. 1, after all, he had passed Ty Cobb for the all-time lead in hits on Sept. 11, 1985, ripping a single into left center before a packed house at Riverfront Stadium.

I was six that year, and the Topps cards that showed up at Rite-Aid in February were around for the year that carried me from kindergarten to first grade, 35 cents a pack for 15 players, some of them superstars, some of them future hall of famers, some of them soon to be fallen heroes.

Two years later, on April 30, 1988, Rose found himself in what would be the second-biggest controversy of his managerial career, making contact with umpire Dave Pallone after Pallone was slow to call Mets center fielder Mookie Wilson out at first on a ground ball to short in the top of the ninth at Riverfront Stadium. While Reds first baseman Nick Esasky was waiting for Pallone’s call, Howard Johnson raced home from second with the winning run.

Rose, incensed, argued the call and pushed Pallone twice, knocking him backwards and earning himself the rest of the night off. Despite Rose claiming that Pallone made contact first, the National League found that Rose had bumped the ump and suspended him for 30 days — still the longest suspension ever handed out to a manager.

That September, “Eight Men Out“ hit theatres across the country, capping a year where three great baseball movies – “Bull Durham” and “Major League” also came out in 1988 – telling the story of the 1919 Chicago White Sox, who took bribes from gamblers to throw the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds and renewing in the mind of the American baseball fan when and why wagering on baseball by those involved in the game became verboten.

The film’s release was well timed. Eleven months later, Sports Illustrated broke the news that Rose had placed bets on baseball while serving as manager of the Reds, and Commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti sent lawyer John Dowd to investigate Rose’s habitual wagering.

Dowd’s report revealed that Rose bet of 52 Reds games in 1987, and on August 24, 1989, Rose accepted a lifetime ban for violating Rule 21(d)(2), which states, “Any player, umpire, or Club or League official or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform, shall be declared permanently ineligible.” By accepting the ban, Rose was placed on the permanently ineligible list, which also made him ineligible for induction to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The rule, which was enacted by Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis in the wake of the Black Sox Scandal portrayed in “Eight Men Out”, has been posted in every MLB and minor league clubhouse for over 100 years to remind players and team staff that the integrity of the game must be unquestionable.

For years, Rose denied betting on baseball, and his supporters engaged in all sorts of intellectual gymnastics arguing why he should not be subject to a lifetime ban, despite clear and convincing evidence provided by Dowd that he had violated Rule 21, which had been on the wall of every single clubhouse he entered as a professional baseball player, from Geneva, N.Y. to San Francisco’s Candlestick Park to Crosley Field and Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati.

For years, Rose tried to play the victim, eventually writing a book titled “My Prison Without Bars” in which he admitted to wagering on baseball, claiming to have only bet on the Reds to win, as if that somehow removes the taint that his actions put on, at minimum, every game he managed and potentially every game he played.

In the 1980s, there was only one place in the United States where wagering on sports was legal: Las Vegas. So outside of Las Vegas, any wager placed on an MLB game (and any other sport other than racing) was illegal, which meant that those who were booking Rose’s wagers were already on the wrong side of the law. Bookmaking has long been a racket controlled by organized crime, so you don’t really have to wonder who was taking No. 14’s action.

And then you have to wonder what those underworld elements thought was implied on the days Rose didn’t call in and place a bet on the Reds, which is where he truly compromised the integrity of the game. A 2015 ESPN report obtained copies of a notebook used by a mob-connected associate who took Rose’s bets, proving that Rose bet while he was a player and committed baseball’s ultimate sin.

Compulsive gambling is a disease that ruins lives; Pete Rose is possibly the highest profile example of this. His lifetime ban meant that as long as he is on the ineligible list, he wouldn’t have a plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame. He never, at least publicly, acknowledged his addiction to gambling nor sought treatment.

In his 1975 book “Charlie Hustle”, Rose casually recounted how he unwound at Florida’s horse and dog tracks frequently during spring training. He was easily the highest-profile horseplayer at River Downs and Turfway Park, two Cincinnati-area tracks, during his playing career.

In his post-ban years, Rose lived in Las Vegas, signing autographs for fans, often with an iPad or laptop nearby so he could bet the ponies. He made appearances across the country and even produced a one-man show where he talked about baseball, never missing an opportunity to pick up some extra cash and rail against the lifetime ban the he accepted in 1989.

Over the course of his 35-year ban, Rose, a Cincinnati-born and raised Reds icon, remained as popular in his hometown as Skyline Chili despite constantly trying to obfuscate all of the bad things he did while playing up his exploits on the field.

I once got a call from his agent, offering me the chance to do a phone interview with the Hit King in advance of his one-man show coming to Albany, N.Y. Over the course of an hour, I could seldom wedge in a question while Pete talked about Pete’s greatness and Pete’s greatest moments. He put on a master class on how to shove the elephant in the room into a closet. When I asked about gambling, the Hall of Fame, and the allegations that he had sex with an underage girl during his playing career, he was less loquacious and somewhat dismissive.

Around the same time, my brother-in-law’s rugby team was holding a fundraiser for ALS research at a local bowling alley. Rose was there, signing autographs for $60 a pop, standing alone clad in a fancy dress shirt and an all-white Cincinnati Reds hat.

When I walked up to pay my $60 to have a ball signed, I saw there was a binder page on the table filled with his 1986 Topps card, No. 1, showing his completed swing, the ball out of frame, presumably rolling fair on Shea Stadium’s outfield grass.

There at the table was baseball’s banished regent, spending a Saturday night in a suburban bowling alley, hawking signed cards and photos of a younger, happier version of himself.

Standing at that table and watching Pete Rose sign a baseball, I didn’t feel as though I was in the presence of greatness. I felt the same as I did standing amongst the railbirds at the Aqueduct or walking through Atlantic City’s casinos, where I could turn my head and see scores of people desperate for a win to get closer to even.

I knew I was in the presence of misery.

Photo: Pete Rose of the Cincinnati Reds inspects his lumber during batting practice at Shea Stadium during the 1980s in Flushing, New York. (Photo by Focus on Sport via Getty Images)