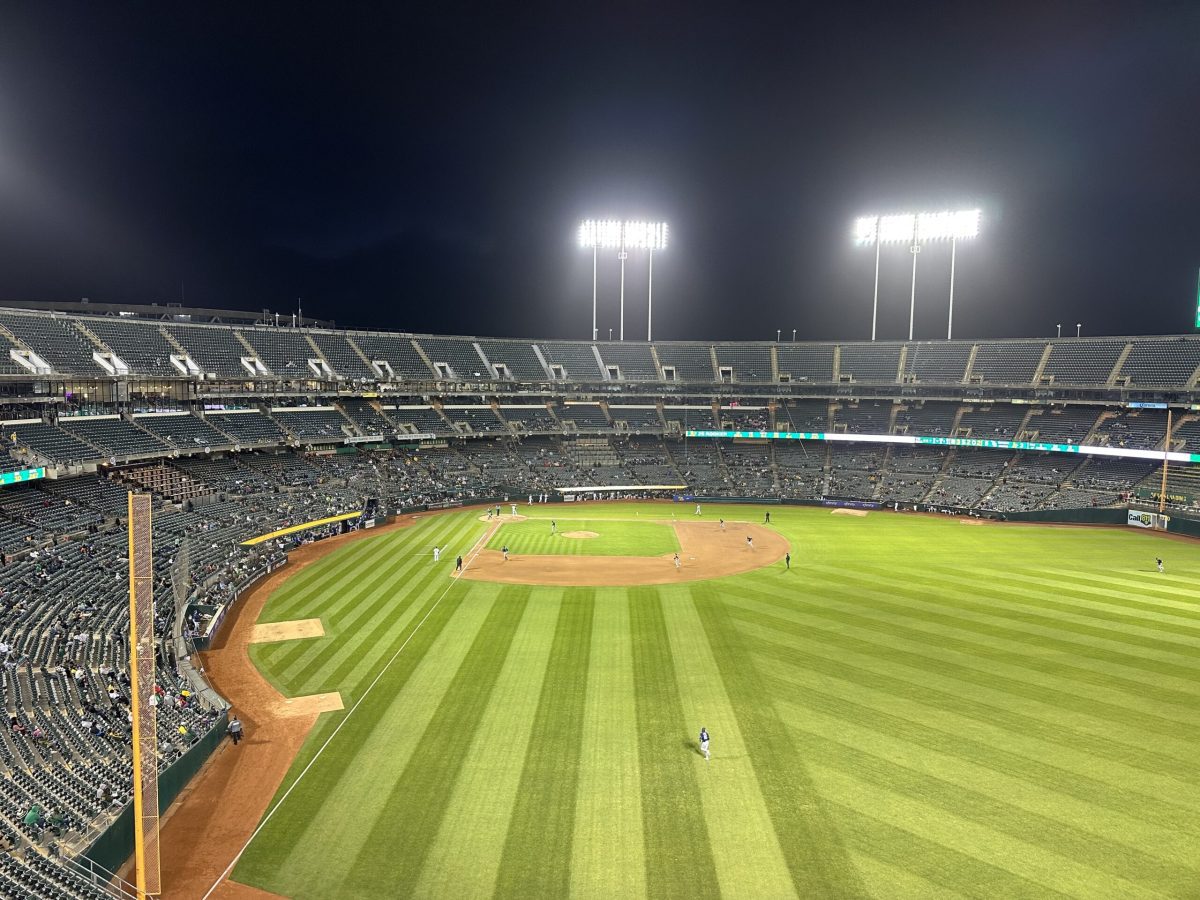

A crowd of 7,055 saw the Tampa Bay Rays beat the Oakland A’s 6-3 on June 15, 2023. (Photo by Leif Skodnick/World Baseball Network)

By Leif Skodnick

World Baseball Network

Editor’s note: This piece represents the opinions of the author and not those of the World Baseball Network.

OAKLAND, Calif – Oakland is neither a city of finance nor glamor. Oakland is a city of industry, a city of labor.

It’s a city where railroad tracks bisect the Embarcadero in Jack London Square, where enormous cranes load and unload stacks of freight containers on colossal ships and lines of trucks extend along the waterfront, where muffler shops installed whistle tips, where the walk across the pedestrian bridge from the BART train to the RingCentral Coliseum, home of the Oakland A’s since 1968, affords one a view of a junkyard, railroad tracks, silos and a facility where colloidal roof coatings are loaded into tanker trucks.

It’s Tupac, not Tony Bennett. It’s Newark, New Jersey, not Manhattan. It’s Carhartt, not The Gap; a gritty, rough-around-the-edges city that loves those who love it for what it is and loves those who love it back.

“Everyone thinks of Oakland and they go, ‘Whoa…’” James Dowling said before Tuesday night’s reverse boycott game against the Tampa Bay Rays. “If I gave you and your wife or whoever an all-expenses-paid trip to Oakland, would you not recoil a bit?”

As an East Coast native who’d never been to the Bay Area before, I didn’t know much about Oakland until I arrived here Monday. But years ago, as a college student in upstate New York, I spent a lot of time watching baseball in a mostly-empty Olympic Stadium in Montreal as the Expos, then owned by Jeffrey Loria and later by Major League Baseball, failed to get a new stadium built in Montreal while simultaneously not fielding a competitive team, driving away the fans until the franchise finally moved to Washington, D.C.

Visiting the Coliseum for the first time this week, I heard that familiar story again.

“A lot of the national narrative is, the A’s have tried here for 20 years, and they haven’t,” Dowling said. “They tried in Fremont, they tried in San Jose. They’ve tried here for a very small number of years. And they keep blaming attendance.”

While the A’s, for years, managed to reach baseball’s postseason with a payroll in the bottom half – and often, in the bottom five – of the Major Leagues, most recently in 2019, the A’s have since parted ways with everyone on that team save for outfielder Seth Brown. The A’s payroll this year is $59,630,474 according to Spotrac, the lowest in the Major Leagues, and until the seven-game winning streak that ended the night the Nevada Legislature approved $385 million in public funds for a ballpark on the Las Vegas Strip, the A’s had the worst record in baseball.

It’s a movie baseball fans have seen before – literally. Remember “Major League?”

To paraphrase a line from another baseball movie: If you don’t build it, they won’t come.

“It’s funny, because we celebrate ‘Moneyball,’ but this is also the result of that, right?” Nathan Pitcairn said outside the Coliseum before Tuesday’s game. “The ‘Moneyball’ approach was a result of not putting money into the team, and not investing into the team, and so Bean and company did what they could, and they did something great and magical, but the ownership never backed them up, you know?”

A century and twenty-one years ago, the man who was soon to become the manager of the Giants was asked his thoughts on the A’s.

Dismissing the question, John McGraw said that he thought A’s owner Connie Mack had a white elephant on his hands; that the A’s, an entry in the upstart American League who then called Philadelphia home, would lose money hand over fist.

Mack took McGraw’s dig with good humor and made the white elephant a symbol of the franchise that he owned and managed for the next 50 years.

The Giants, who then played in New York, and the A’s built a rivalry long before both teams abandoned the east coast for the Bay Area, with each franchise reaching the World Series five times between 1905 and 1913. The A’s won three, including two championships against the Giants in 1911 and 1913, while the Giants beat the A’s in 1905.

In the 1980s, the elephant again became an emblem of the A’s, and has adorned their green and gold uniforms ever since. Not long after, the A’s got the better of the Giants in the 1989 World Series, the fall classic famously punctuated by the Loma Prieta earthquake minutes before the start of Game 3.

And in a year or two, or possibly less, when the A’s are gone, having moved for the third time in their history, the City of Oakland will be left with the ultimate white elephant: a dated sports complex with no tenants, one that used to be a team in each of North America’s four major leagues, all having moved away or folded.

John Fisher, heir to a fortune that the ubiquitous mall clothing store The Gap founded by his parents piled up, owns the A’s. He inherited the money, he made the investment, he holds the equity in the franchise. With the team playing in a new stadium, he’ll likely be able to sell the team for a tidy profit.

But surely the fans’ memories, the civic pride, the family bonding time – that should count for something, right? As Ted Lasso, the football-turned-soccer coach played by Jason Sudeikis in a popular series name after the character said when he decided to allow fans to watch the team practice, “It’s their team, we’re just borrowing for a while.”

“The day that they announced that they were focusing solely on Vegas, every one of my family cried, and I was late for work because I had to console my kids. Taking the team out of Oakland is taking generations of bonding,” Roberto Santiago said outside Tuesday’s game.

The message Oakland has, for John Fisher, for Major League Baseball, and for the sports world according to Santiago, is simple.

“We exist, and we’re here, and if you bring a winner, and if you bring an owner who’s invested in this community, we will pack this place. this community, we will pack this place. Absolutely.

Outside Tuesday’s game, Santiago recounted to me how his dad took him to games, and how he didn’t know what to do with his brother, 13 years younger, so he took him to A’s games. How his family would go to Opening Day together every year. How his grandmother would get free tickets from the senior center and drop him off at the Coliseum. She’d know when to pick him up because she’d listen to every game on the radio and head back in the middle of the eighth inning.

Santiago’s grandmother went 20 years without seeing an A’s game in person, and then he brought her to a game that featured perhaps the most iconic play ever made in a baseball game played in Oakland: Derek Jeter’s infamous flip in Game 3 of the 2001 American League Division Series.

“My dad gave it to me, and I gave it to my brother, and I gave it to my kids, and I wanted my kids to give it to their kids,” Santiago said. “Baseball is beautiful, and baseball is generational, and baseball is everything that the most romantic essays on baseball that have ever been written [have said] – it is that. And it’s still that.”

But damn, baseball – especially Major League Baseball, and the big business that it is – sure can break your heart.